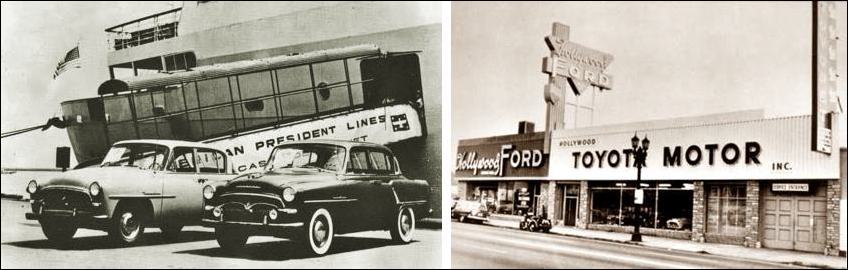

“If Toyota or other Japanese manufacturers had concentrated on making large automobiles like the American ones, World War III might have started!”

It was 1983 and the person who made the statement, more as a joke, was Hiroshi Okuda, then a senior executive of Toyota Motor Corporation in charge of Asian markets (and later President, then Chairman of the company), who was responding to a question I raised about why Japanese companies had concentrated on small cars rather than larger ones.

Perhaps Mr. Okuda, whom I met in August that year, had not yet attended a top secret meeting in Toyota City which was of monumental significance to the company. At that meeting, said to have taken place the same month, Chairman Eiji Toyoda declared that the company should make a new luxury model for export – and it had to be comparable or better than the best German luxury models.

The company, which was nearly 50 years old, did have one very large and exclusive model known as the Century which had been on sale since 1967. It was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Sakichi Toyoda, father of Toyota’s founder, Kiichiro Toyoda, but it was never considered suitable for export because the design was deemed unlikely to be appealing outside Japan. In any case, the Century was never sold in large numbers and mainly used by top executives of the company, very senior people in other companies and government officials.

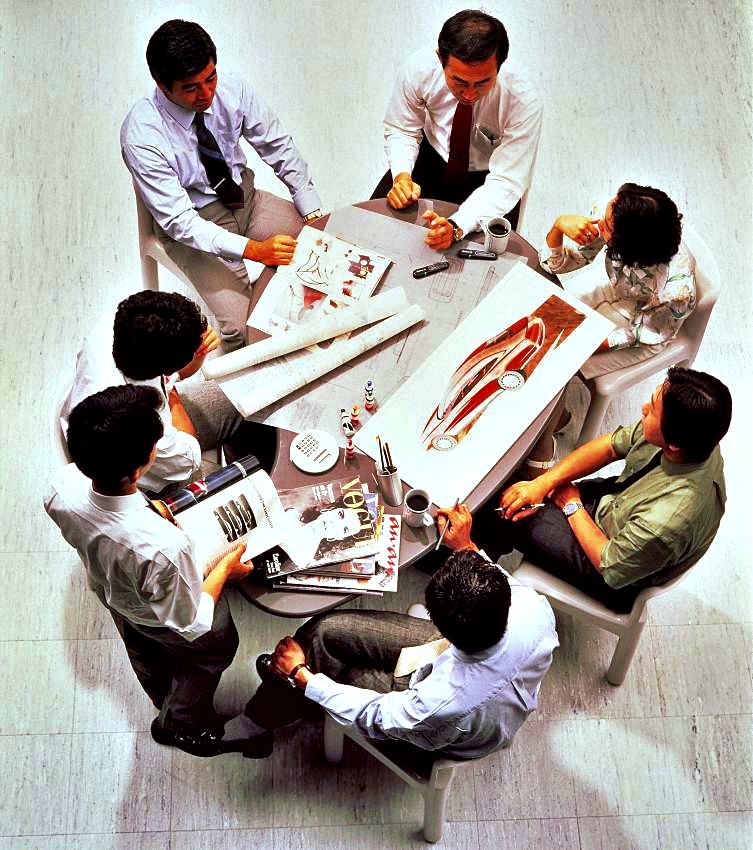

By early 1984, a broad outline was prepared and top management gave its approval for the project team known as ‘Circle F’ (for Flagship) to begin work on an entirely new type of car never before sold by Toyota. The initial idea to develop something along the lines of an upgraded Crown, then Toyota’s largest export model, was immediately dismissed. The new model had to be good enough to challenge the cream of the world market and had to be entirely new.

![Toyota Crown [1986]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Toyota-Crown-1986.jpg)

Focus groups were organised in 5 major cities and out of the 22-month research, what the luxury car buyer looked for became clear in this ranking: prestige, safety, resale value, performance and styling. It became very obvious that image was crucial in the luxury car buyer’s mind; Mercedes owners bought the German car because it was prestigious.

But there was a glimmer of hope for Toyota because many people were not against buying a Japanese luxury car – provided it was prestigious enough to be seen in one. This would later become a major reason for creating a new brand distinct from Toyota.

While Toyota cars were respected for their high quality and reliability, the brand image was simply inappropriate for a luxury car. Though there was a worry that the Toyodas would regard it as insulting to say their brand name was ‘not good enough for a luxury car’, the decision was made quite quickly because it was understood that the target customers would not accept a Toyota-branded luxury model – even if it was better than a Mercedes or BMW.

And who were the people Toyota expected to sell this new car to? Definitely not those who typically bought Cadillacs but not necessarily the ‘yuppies’ who became a recognisable group in the mid-1980s. The target buyers were also ‘baby boomers’ (the generation born after World War II) but, unlike yuppies, they were not as image-conscious and instead more practical people. In their 40s, they sought products which were good value because it showed that they were able to make smart decisions in their life.

Having figured out who they were designing for, the next step was to work on styling. Calty (Toyota’s advanced styling studio in California) was already exploring an upmarket model and this gave the designers a starting point for the model which would later be coded ‘F1’ by its chief engineer.

In August 1985, five Japanese designers started work with two American ones at Calty. To help the Japanese appreciate American living spaces and relationship to car spaces, the Calty people built a mock-up of an American home and this helped in design considerations tremendously.

Many decisions on design were still made in Toyota City and Japanese designers had no real ‘feel’ for the American way of life and the expansive spaces. Remembering that the very first Toyota cars sent to the US had not been engineered for the long freeways with higher speeds than Japan, it was crucial that the new model was exactly right for the American market.

This led to a Japanese team of product planners being sent to live in the US for a few months to observe and experience the American lifestyle which was a great difference from their own. They not only experienced daily motoring conditions but also the various social and recreational activities.

All the initial ideas were rejected by the top management and it took another 16 months before a shape was agreed upon, an indication of how vital it was to get the car right. Only in May 1987 – just over 2 years before the car was to be launched – was final design approval granted.

![Lexus LS 400 [1990]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Lexus-LS-400-1990.jpg)

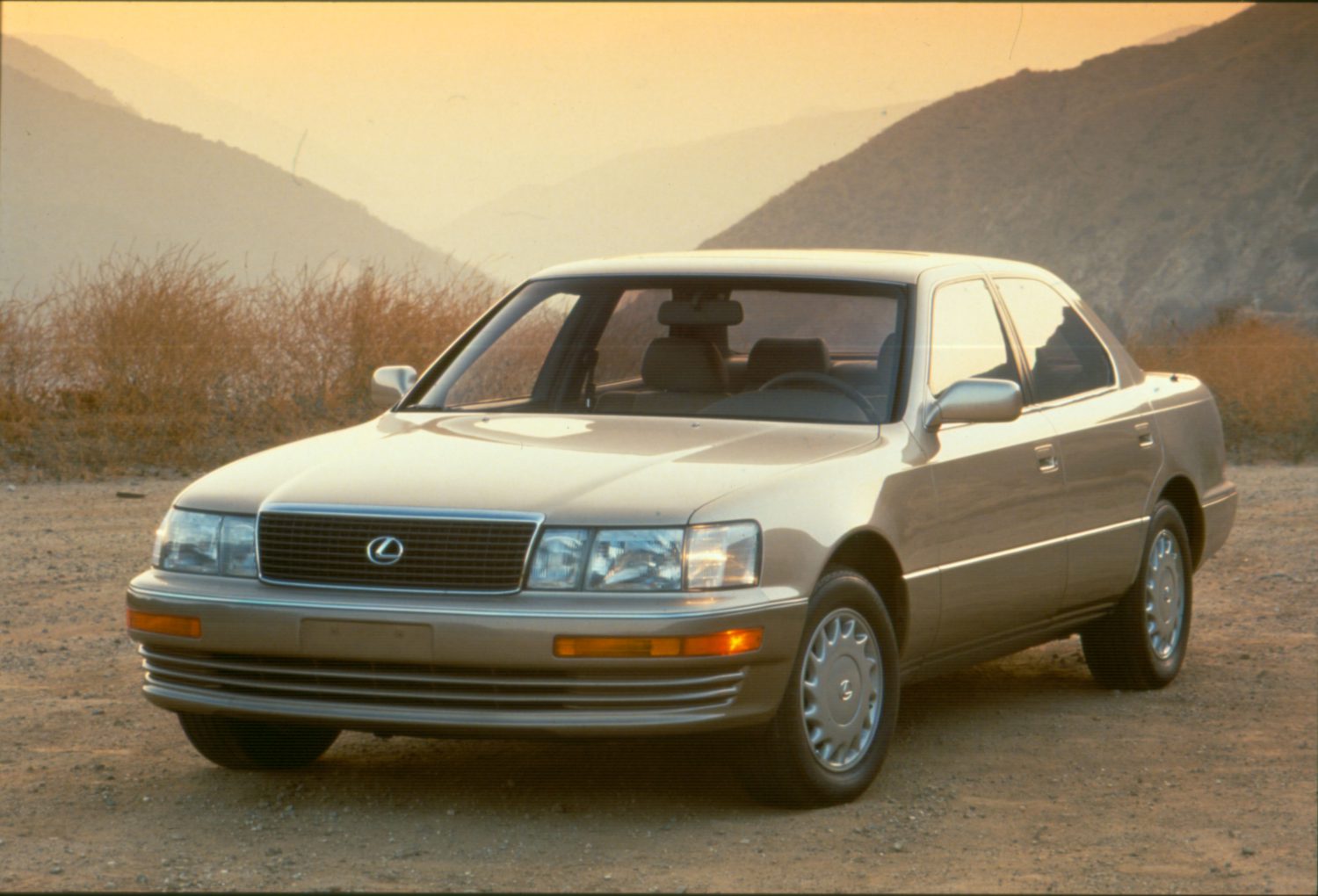

It had been a tough battle between the American side which was against the conservative style that the Japanese side favoured. A major point of contention was the frontal appearance of the car, specifically whether or not a grille was to be present. To look ‘advanced’, most of the stylists did not want what was considered an old-fashioned embellishment. However, when they looked at the cars being challenged, all had distinctive grilles. So there had to be a grille if the car was to be ‘a luxury car’.

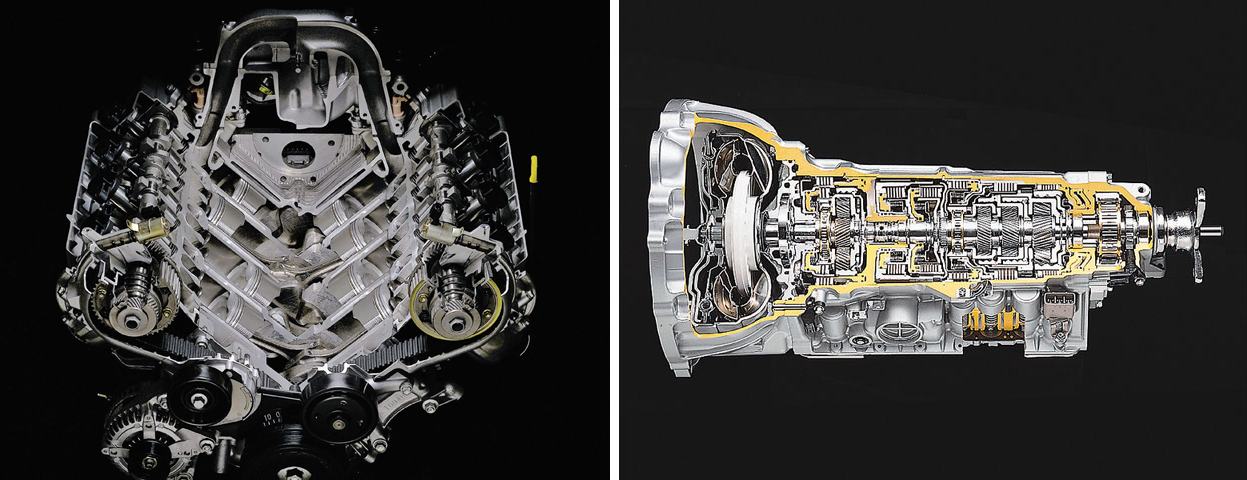

In March 1985, the engineering team (the whole project involved 1,400 engineers) began examining what went into the other luxury cars and bought various Mercedes-Benz and BMW models. Money was not a problem for them as Toyota was by then making US$30 billion in net sales annually and spent 5% of that amount on R&D each year. That’s plenty of money to buy cars!

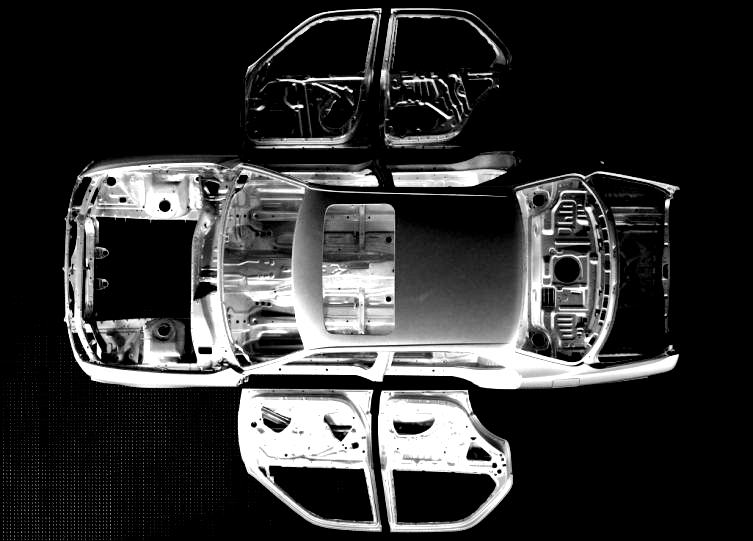

Every component in the German cars was studied and the best parts became not just benchmarks but minimum standards; for the new car, Toyota wanted to make and use even better parts than the best in the world!

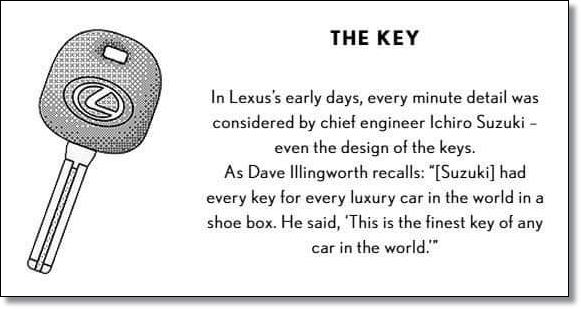

In February 1986, Ichiro Suzuki was appointed as the new Chief Engineer of the model. Having Suzuki as chief engineer made a lot of difference because he was a body structure specialist. From the outset, he decreed that quietness would be achieved not by masking it with thick layers of sound insulation but by eliminating the very source of the noise. Since most of the noise and vibrations came from the powertrain, the engineers examined it in detail and used new materials and ideas liberally for silent and smooth running.

Their most impressive effort was probably the driveline and differential. Here, the two-piece propshaft was arranged in a very straight line with a high-precision universal joint in the centre and flexible couplings at either end to compensate for even the slightest deviation.

Another key decision was to keep the car’s weight under 1,818 kgs in order to avoid the US luxury car tax and to be within the 25 US mpg (10.6 kms/litre) threshold to avoid the ‘gas-guzzler’ tax. Weight was so strictly controlled that only Suzuki – who took his job so seriously that he was seen as obsessed with perfection – could approve any change that added 10 grams extra. In the end, it tipped the scales at 1,708 kgs.

![Toyota FXV-II [1987]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Toyota-FXV-II-1987.jpg)

Over 450 test cars were built and driven a total of more than 1.6 million kilometres in different countries. Early engineering prototypes disguised as Cressidas and Crowns were flown to Germany for high-speed testing on the autobahns to confirm the target speed of 240 km/h could be attained. It was amazing that there were no rumours of a new luxury model from Toyota all the while.

![Lexus LS 400 [1990]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/1989-Lexus-LS-400-3.jpg)

Six months before the launch in January 1989, an undisguised prototype was driven, from Los Angeles to Chicago and then to Florida by Suzuki himself who wanted to be certain that everything was just right. The car attracted some attention along the way and at one petrol station, a curious motorist was told that it was a ‘new Mercedes’!

Having designed a car that looked like it would be able to take on the world’s best, the next challenge was to give it quality levels higher than anything Toyota had ever achieved. Toyota had already redefined quality and was a master at less tangible forms of quality which opened a new, but more subtle, gap with other carmakers. Everything, from the unique mica paint finish to the selection of leather for the upholstery to a special ‘anti-aging’ process used, was applied to produce what would be later recognised as the best-built car in the world.

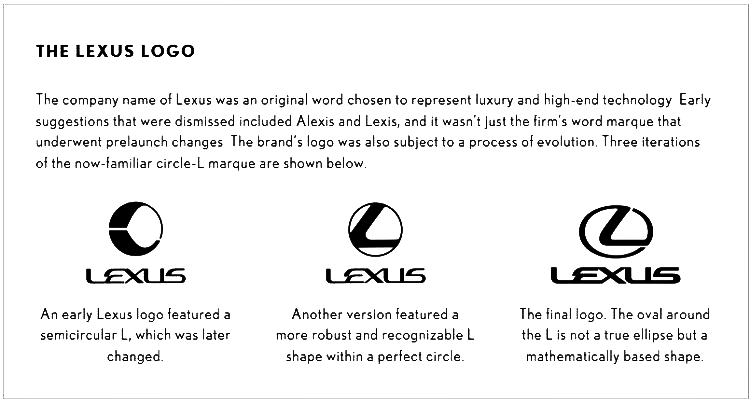

The decision to have a second brand led to having a second sales channel altogether. Over 200 names were proposed, including ‘Alexis’ which was also the name of a character in the ‘Dynasty’ TV series at that time. ‘Alexis’ was favoured by the committee responsible for choosing the name but its association with the TV character who had a scandalous image made it unacceptable (apart from sounding feminine).

The other ‘finalists’ were Calibre, Chaparel, Vectre and Verone; Lexus was actually created from ‘Alexis’ after the project manager played around with the letters. So, while many brand names have some meaning, Lexus actually has no particular meaning.

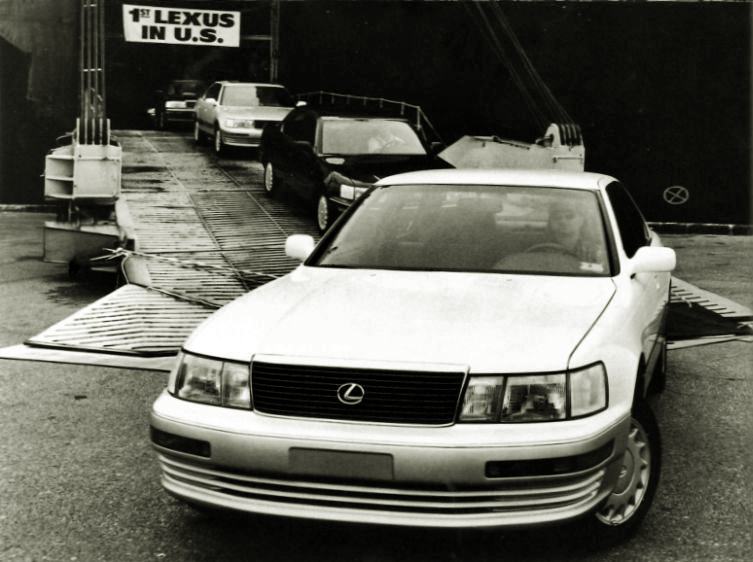

![First Lexus in USA [1989]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/First-Lexus-in-USA-1989.jpg)

Sales began in September 1989 with two models – the LS400 flagship which was the focus of attention, and the Camry-based ES250. The LS400 cost US$35,000 (RM85,500 at that time), US$19,000 less than a BMW 735i and US$26,000 less than a Mercedes-Benz 420SEL which were comparably equipped.

The launch of Lexus was not without some awkward moments, one of them being a lawsuit from a firm which had almost the same name (Lexis) virtually on the evening of its launch in Detroit. “It was really crazy when it happened and we had to go to court hearings at a time when we were very busy setting up Lexus all over the country,” Takahiro Honda, one of the Toyota executives who was involved in the legal battle, told me a couple of years later. The court ruled in favour of Toyota, giving Lexus extra publicity at no charge (Lexis was ordered to pay Toyota’s legal fees as well).

Less than 3 months after the cars went on sale, problems surfaced and about 8,000 LS400s had to be recalled immediately as two were safety-related. One problem was loose battery cables while the other two were the wiring of the third brake light that was sub-standard. The third was the most worrying – a problem with the cruise control.

For the quality-proud Japanese, especially with a product claimed to be superior in that respect, it was embarrassing. But what could have been a potential blackmark became something owners would always remember and tell their friends – in a very positive way.

All owners were notified by telephone and those within 160 kms of a dealership didn’t even have to bring their cars in. The dealers sent technicians to their homes to fix the problems at no charge, returning the cars washed and polished with a full tank of petrol. The handling of the recall became legendary and the standard that other manufacturers often try to match. So even in recalls, other companies are being judged by how Lexus did it!

And what did the competitors think about the newcomer? Initial official reactions from Mercedes-Benz and BMW were indifferent, bordering on arrogance. After all, what did Toyota know about making luxury cars? The two German companies were not so concerned but still attacked Toyota for the pricing levels of its model. The Germans believed that Toyota was prepared to sell the LS400 ‘at a loss’ for a few years to drive them out of the market.

Toyota maintained that they made a ‘reasonable profit’ on the LS400 and retorted that the Germans were annoyed because it was shown that a luxury car could be made for less money than what buyers were led to believe. In the words of Keith Crain of Automotive News (the leading industry publication in the USA): “Lexus has changed the price-value relationship; it is no longer enough to build the best cars in the world if they have to sell for US$60,000 to US$100,000”.

Of the product itself, Mercedes-Benz found it to be ‘competently engineered’, like other Japanese cars, but still would not consider it a worthy rival. Most journalists thought otherwise and Autocar, when testing the Mercedes-Benz 600SEL V12, chose only the LS400 for comparison and declared that the Japanese car was actually smoother.

The comparison offended the people in Stuttgart, and the PR manager of the German company told me that he had asked Autocar why they had been so unfair to use a car which was surely in ‘a different class’ from the 600SEL. The reply was that the comparison was being made between the flagships of two companies. Later on, Autocar also did a comparison test of the LS400 with the then-new BMW V8 7-Series and found it difficult to conclude totally in favour of the BMW and almost recommended both cars equally.

![Lexus LS 400 [1990]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/1989-Lexus-LS-400-1.jpg)

Mercedes-Benz therefore quietly decided to find out just what made the car so good and why people were saying it was better. I saw one of the two LS400s they bought when I was at the Stuttgart testing grounds some years later and when I asked one of the engineers why there was such interest, he admitted that the drivetrain was very impressive and they wanted to see if it had a breaking point (among other things, I suppose).

Before I went off and started saying that engineers in engineering-proud Mercedes-Benz were admitting that the LS400 was better, he quickly added: “it obviously has a long way to go… Lexus has no heritage to speak of and lacks character”.

The absence of heritage was true and so was the lack of ‘character’ which often came to be blamed because the LS400 was ‘too perfect’. But that didn’t stop the brand from being the fastest in automotive history to become established in the luxury segment and even 17 years after being born, its products and services remain industry benchmarks.

[This article was originally published in 1997 in Highway Malaysia magazine]

![Lexus LS 400 [1990] Lexus LS 400 [1990]](https://www.motaauto.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/1989-Lexus-LS-400-4-696x452.jpg)